Vladimir Staroselsky - Country of Liquid Sun

Wednesday, May 6

Vladimir Staroselsky was born in 1860 into the family of poor nobleman from Chernihiv. His father, Aleksander Staroselsky, was in military service until 1850. After that, he served as a low-rank official in the judicial authorities of various provinces of Russia, including Armenia and Georgia. Aleksander Staroselsky, who was distinguished by his honesty and diligence, was the brother of Tadeoz Guramishvili's brother-in-law and Ilia Charchavadze's brother-in-law, Dmitri Staroselsky, and often visited Ilia Chavchavadze in Saguramo together with his family.

This circumstance connected Vladimir Staroselsky with the Georgian people since his young years which, alongside other factors, contributed to the formation of his love and selfless friendship towards Georgians, he was devoted to this feeling until the end of his life.

After finishing the Stavropol Gymnasium with honors, Staroselsky continued his studies at the Moscow Academy of Forestry and Agriculture (now the Timiryazey Agricultural Academy) from which he graduated with honours in 1885. Immediately upon graduation, he was sent to the Black Sea District where he attracted attention by his erudition, scientific research and organizational talent.

In 1888, Staroselsky was transferred to Tbilisi as a Senior Agronomist of the Caucasian Division of the Ministry of Agriculture and State Properties. It was the period when grape vine disease-phylloxera-infiltrated from the West and was spreading extensively in various regions of the country, instantly devastating vineyards. The first of phylloxera was discovered in Georgia in 1881, in Abkhazia. The disease spread so quickly that it covered not only Georgia but its neighbouring countries within several years.

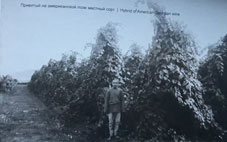

As for the idea of grafting vines on American base plants, first offered by Staroselsky, the majority of specialists, as well as the Ministry of Agriculture and State Properties, treated the idea with complete distrust. This distrust was strengthened by the negative opinion of the French Professor Morigno, the Hungarian scientist Horvaty, the Russian Professor Kovalevsky and other prominent specialists in regard to this method. They examined the vineyards diseased with phylloxera in the Upper Imereti districts and categorically denied every possibility for their restoration. At the same time, the Ministry of Agriculture of Russia invited additional scientists and specialists from Europe who studied the vineyards which were damaged by phylloxera and made their conclusion. In their opinion, it was already impossible to restore vineyards in Imereli. They stated that the Georgians would have to exterminate the vines and plant other vines or different crops instead. Staroselsky did not retreat from his position and insisted that the Georgian vineyards should be transplanted onto American base plants. Further, he also insisted on the necessity of the implementation of this method and the perspectives which would follow.

In 1890, Staroselsky was appointed Chief Expert of the team working to fight the phylloxera disease in of the Kutaisi province. By that time, the vineyards ultimately damaged by phylloxera were located in this area alone. The product of the hard work of the local peasants, which was their basic subsistence, was disappearing and the desperate peasants demanded help. Staroselky began activities with his usual energy and achieved excellent success in a short period of time.

That same year, an experimental seedling farm was established in the village of Sakara, near Zestaponi, on Staroselsky's initiative and under his direct leadership. It soon turned into an important centre of scientific research and popularisation of its results. For five-to-six years, the area of the Sakara Seedling Farm grew from 2,000 square meters to 18 hectares and its supply of young plant materials also greatly improved. Staroselsky, as the founder of the experimental farm, was sent on assignment to France, Switzeriand and Austro-Hungary where he fundamentally studied the current issues of viticulture and wine making which including experimental methods to fight vine diseases; making him more and where he became more confident about the advantages and future perspective of his own ideas related to the promotion of American vines.

Staroselsky enjoyed great popularity, trust and overall respect amongst the Georgian intelligentsia, public figures and, in particular, the peasants of West Georgia. For these very reasons, the newly-appointed Tsar's Governor, Count Vorontsov-Dashkov, prior to his arrival in Tbilisi in March 1905, offered Staroselsky-who was in St-Petersburg on occasion-the position of Kutaisi Governor. Staroselsky refused the offer. He reasoned his refusal, primarily, by the circumstance that the position would not allow him to continue his scientific research activities and that his personal qualities were not suitable for the functions of a high-positioned administrator such as a Governor. Nevertheless, Vorontsov-Dashkov's decision was firm. Influential officials, like the assistant to the of Tsar's Governor, Sultan Crimgirey, who was known for his liberality, also advised favourably upon Staroselsky's candidature.

Previously, General Smagin, a devoted servant of monarchism, headed the province of Kutaisi. On 21 May 1905, he was relieved of his official duties with Vorontsov-Dashkov proposing Staroselsky's candidature to St-Petersburg on 7 June. There was quite a bit of hesitation at the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Tsar's Palace. The delay lasted for more than a month but they finally took the opinion of the Tsar's Governor into consideration with Emperor Nikolai II signing the resolution regarding the appointment of Vladimir Staroselsky as Acting Governor of the province of Kutaisi on 9 July 1905.

Under the influence of Governor Staroselsky, repressions against the revolutionist movement and party organisations were suspended step-by-step. At the beginning of August, he issued the order to prevent police authorities from taking any measures against anti-governmental meetings, manifestations with red flags and the spreading of revolutionist leaflets. On 8 January, Emperor Nikolai II sent a personal letter to the Tsar's Governor in Caucasia, advising Vorontsov-Daskov to take extreme measures for the suppression of the revolutionist movement. The second part of the letter referred to Crimgerey and Staroselsky. Vorontsov- Dashkov established a special commission under the leadership of his assistant, Senator Mistkevich. The commission went to Kutaisi, performed on-situ investigation and collected a great deal of materials about the convictions against Staroseisky. A military investigation commission performed activities at the same time. According to the conclusion of the both commissions, Staroselsky, obviously, had betrayed the Tsar's government, supported the revolutionist movement and facilitated its spreading and development.

It would be logical to impose responsibility upon Staroselsky for this crime and execute him by hanging. At the end of January 1906, however. Vorontsov- Dashkov released Staroselsky from house arrest and only evicted him from Caucasia. Later, in June 1906, the Tsar's Governor stopped the proceedings related to Staroselsky and left it for good.

There was no time for delay. Staroselsky left for St-Petersburg on the very first train. Early in the morning, policemen rushed into his flat, but without any result. The administration, upset by the news, sent this information to Tbilisi and St-Petersburg by telegram. They were searching for the criminal Governor but there was no trace of him to be found. Staroselsky, who had changed his clothes and made himself up in disguise, was already headed by ship towards Marseille where he secretly got on board and planned to go to Paris.

Why did Vorontsov-Dashkov display such a strange mercy towards the revolutionist Governor? What caused him to even ignore the Emperor's instructions? We have to suppose that Vorontsov-Dashkov's personal sympathy towards Staroselsky played a leading role in this case.

Staroselkys' only son could not endure parting with his father and his unfair persecution in the Tsar's Russia. On 15 May 1909, Boris Staroselsky committed suicide and shocked his mother, Nadezhda Staroselskaya, who was in despair. Despite the tragedy, Staroseiskaya went to Paris to join her husband and comfort and support him.

Staroselsky, left without any means of subsistence, began to work as a photographer in Paris and soon became famous although it was hardly enough to live on. Difficult work, overall difficult conditions and his concern about his family which was in a helpless situation undermined his health at an early age. Staroselsky died in Paris on 6 August 1916, a lonely man, at the age of 56.

On 29 August, the mourning columns consisting of French communists, socialists, Parisian workers and friends came to see off Vladimir Staroselsky's body to the communards graveyard. There were flower garlands with inscriptions reading "To a citizen and defender of proletarians.” There also was one wreath with an inscription which read "To our Patron -From a grateful Georgia".