1821-2021: 200 Years of the Greek Revolution

Thursday, March 25

Greece celebrates 200 years since the outbreak of the Greek Revolution in 1821, an event that created the independent Greek state and secured freedom of the Greek people after centuries of Ottoman rule. The Greek Revolution was a pivotal historical event, the first successful uprising against the Ottoman Empire, with considerable repercussions in Europe and the Mediterranean.

An Outline of the Revolution Events

The Greek Revolution of 1821 was a long struggle that led to the creation of the independent Greek state, Hellas. Before the outbreak of the Revolution the Greek population resided in two major geographical entities:

i. the historical Greek space comprising modern Greece, Cyprus, the western coast of Asia Minor, Constantinople, and the Pontus region in the Black Sea;

ii. the centres of Greek Diaspora, with the most important among these being the Moldavia and Vlachia region in modern Romania, the communities around the Black Sea and the urban centres in Egypt. It is indicative for the dynamism of these Greek communities that the Revolution itself was planned in Odessos of modern Ukraine and begun in the region of modern Romania.

The Revolution was initiated in February 1821 in Moldovlachia, modern Romania and Moldavia, on 24 February 1821, when Alexandros Ypsilantis and the Sacred Band, a group of warriors, raised the flag of Revolution. Ypsilantis issued his seminal declaration ‘Fight for your faith and country’ calling on all Greeks to take up arms to defend their Christian and Hellenic identity. In mainland Greece the Revolution broke out in March 1821 in Peloponnesus, the southernmost part of continental Greece, and soon expanded to the islands of the Aegean Sea and other regions of continental Greece, Thessaly, Epirus, and Macedonia. Experienced warriors and able seamen took up the burden of the fight against the Ottoman Turkish forces. The mountainous formation of Greece and spatial fragmentation in isolated valleys facilitated the activities of the revolutionaries. Greeks fought fiercely for seven years knowing victories and defeats. The Ottoman fleet destroyed many islands killing and enslaving the local Greek population (Chios 1822, Kasos 1824, Psara 1824), while joint Ottoman and Egyptian forces landed in Peloponnesos -the geographical core of the Revolution- threatening to suppress the Revolution.

The three major Grand Powers of the time (Great Britain, France, and the Russian Empire) which so far had exerted only diplomatic pressure on the Ottomans, decided to intervene to reassure a kind of autonomous status for Greeks. The naval Battle of Navarino in 1827 and the dispatch of a French expeditionary corps in Peloponnesus the next years safeguarded the autonomous political existence of Greeks. Still an independent Greek state became a reality only after the disastrous outcome of the 1828-1829 Ottoman-Russian war. In 1830 Greece was born as a free state of the Hellenic nation.

Factors of the Revolution

The Revolution was based on a multitude of different social strata that united in achieving their goal of a modern and independent Greek state. The main actors involved were:

i. the warriors, known in Greek as kleftes and armatoloi. These were irregular militia with considerable war experience due to their constant strife against the local authorities of the Ottoman Empire.

ii. merchants chiefly located in the islands of the Aegean, such as Hydra, Spetses and Psara; merchants controlled the flow of capital from the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea and up to coastal Western Europe along the axis of the Mediterranean Sea.

iii. local political leaders with power under Ottoman rule who helped coordinate the population.

iv. the Church and intellectuals. The Orthodox Church with its priests was pivotal in preserving the morale of the warriors and the population during the struggle. Intellectuals influenced by Western ideas helped introduce in Greek thought the notion of a modern Western-type Greek state.

The Orthodox Church and the Greek Revolution

The clergy participated actively in the uprising of the Greek population against Ottoman oppression. Simple priests, bishops aided the rebels, motivated the population with their lectures and preserved the morale of the ailing Christian Greek population that was subject to atrocities by the Turkish side.

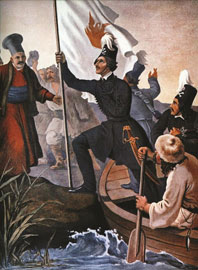

During the centuries of Ottoman rule many bishops and Patriarchs lost their lives for their defence of the Christian faith against abuses of the Ottoman state. Hundreds of priests were killed and martyred just for being Christians during the Ottoman rule. Greek national conscience was nurtured and strengthened in schools run by the clergy. Saint Kosmas Aitolos founded numerous schools and preached arousing Greek conscience before the Revolution. Bishop Palaion Patron Germanos prepared the outbreak of the Revolution in Peloponnesus. The day was initially scheduled to coincide with 25th March, the Day of the Annunciation, an important festive day of the Orthodox Greeks. Events unfolded faster with clashes between Greek rebels and Turks in various places. The Patriarch of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and leader of the Greek population, Gregorius V, was hanged by the Turks in April 1821, another martyr of the Greek Orthodox community.

The Orthodox Church was essential in preparing the Greek Revolution and preserving the historical identity of the Greeks, a faithful Christian people that kept its cultural and religious references for centuries in the harshest conditions of Ottoman rule.

Prominent Figures of the Revolution

The Revolution featured a multitude of brave individuals, both men and women, who gave up everything, often their lives and their fortunes, for the freedom of the Greek nation against all odds at the time.

Alexandros Ypsilantis, the leader of the Philiki Hetereia (‘Company of Friends’) since 1820, a secret society that prepared the Greek Revolution. Ypsilantis formed the Sacred Band and issued the Declaration of the Revolution on February 22, 1821.

Theodoros Kolokotronis was the greatest general of the rebels, a strategic genius hailing from a family with life-long struggles against Ottoman rule. Kolokotronis was responsible for many decisive victories and kept the flame of the Revolution alive in its darkest hour when all seemed lost.

Nikitas Stamatelopoulos having served in the French and English army was an experienced commander and an expert in guerrilla warfare against the superior Ottoman forces.

Athanassios Diakos was an Orthodox deacon and military commander defeating the Turks in mainland Greece near the ancient battlefield of Thermopylae where Greeks had stood up against another Asian invader. He was martyred early in 1821.

Konstantinos Kanaris was the most prominent admiral of Greek rebels during the Revolution. His expertise as a naval commander was fundamental in gaining control of the Aegean Sea by the Greek rebels against the stronger Ottoman fleet. He later served many times as the Greek Prime Minister.

Women in the Greek Revolution

Laskarina Bouboulina was a legendary Greek naval commander and heroine of the Greek Revolution. Born in the prisons of Constantinople Bouboulina became a member of the Philiki Hetaireia, the secret society that prepared the Revolution. She spent her entire fortune to aid the Greek Revolution buying arms and ammunition for a warship and supplying for the Greek soldiers under her command.

Manto Maurogenous was the daughter of a rich merchant. She used her vast fortune to prepare warships against the Ottoman forces and pirates and to aid the Greek population that was starving after the attacks of the Ottomans. She also issued declarations to the women of Europe to help the Greek people in their righteous struggle against the Ottoman Empire. She died poor having spent her entire fortune for Greek freedom.

Greek National Anthem

The national anthem of Greece and Cyprus is composed of the first two stanzas of the Hymn to Freedom (1823) composed by the poet Dionysios Solomos. This is the 1918 translation by the British poet Rudyard Kipling:

We knew thee of old,/O, divinely restored,/By the lights of thine eyes,/And the light of thy Sword.

From the graves of our slain,/Shall thy valor prevail,/ as we greet thee again,/Hail, Liberty! Hail!

Philhellenism during the Greek Revolution

Philhellenism (‘the love for Greece and Greek culture’) was a prominent ideological current among Western intelligentsia and the general population based on the perception of classical Greece and the struggle of the Greek nation to obtain its freedom after centuries of barbaric Ottoman rule. Philhellenism had already manifested itself in literature, art, and architecture with the spread of Classicism and Hellenic themes. During the Greek Revolution it became a living reality with the support of struggling Greeks. Many prominent writers and artists supported the Greek Revolution: the French Victor Hugo, Francois Chateaubriand and Eugene Delacroix, the Russian Alexander Pushkin, the German Friedrich Schiller, the American Daniel Webster, the English Percy Shelley and Lord Byron, the famous Romantic English poet, who lived and died alongside the Greek rebels.

Even since its first days the Greek Revolution created waves of sympathy among various nations, both in Europe and the rest of the world. Support for the cause of the rebels was manifested in various ways. In many capitals and cities of Western Europe people and officials gathered money and valuables to aid the Greek rebels. The King of France, Charles X, and the King of Bavaria, Ludwig I, father of Otto I, who would later become the first Greek king, supported generously the Greek Revolution with financial means. Volunteers from all over Europe, especially Germany, Italy, France, England, Poland, and even from the Americas came to Greece to fight for the freedom of an ancient nation.

Hellas, the free Greek state

Greece (Hellas) was founded in 1830 according to the provisions of the London Protocol. The new independent state had a limited territory of 47,476 square kilometres. Greece was founded at the southern tip of the Balkan Peninsula with the regions of Peloponnesus, Sterea Hellas and the Cyclades as its territorial core. Greek territory would later expand to include Thessaly, Macedonia, Thrace, and the islands of the Aegean Sea. Greece was for a long period the only Western-type state in the Balkans and the Mediterranean.

Today, 200 years after the Greek Revolution, Greece is a modern state of 11 million people with a high standard of living. Greece is a proud member of the European Union and NATO, a dynamic actor in the Mediterranean Sea establishing new networks of regional cooperation.

Ioannis E. Kotoulas, Ph.D.

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

![Bishop Palaion Patron Germanos blesses the Greek revolutionary flag and rebels swear to fight or die for Greek freedom [Painting by Theodore Vryzakis, 1865]](1.jpg)

![Bishop Palaion Patron Germanos blesses the Greek revolutionary flag and rebels swear to fight or die for Greek freedom [Painting by Theodore Vryzakis, 1865]](1.jpg)

![Bouboulina, legendary woman naval commander of the Revolution [Unknown painter, late 19th century]](3.jpg)