Could he lose?

Friday, November 30

When Mikheil Saakashvili called for a snap presidential election after a violent crackdown on anti-government protests plunged the country into a severe crisis, most observers named him the odds-on favorite to win a second term against a scattered field of opposition candidates.

Now, with just five weeks to go to the January 5 election, some polls suggest he may face an unexpectedly serious challenge staying in office.

Saakashvili, who swept to power in the 2003 Rose Revolution and was elected president in 2004 with 96 percent of the vote, has seen his popularity slide in the last year as vigorous economic reforms pleased Western supporters but left many Georgians feeling left behind.

Early successes for the Saakashvili administration included effectively eradicating low-level corruption, attracting major foreign investments and collapsing the separatist-minded regime of Adjaran dictator Aslan Abashidze.

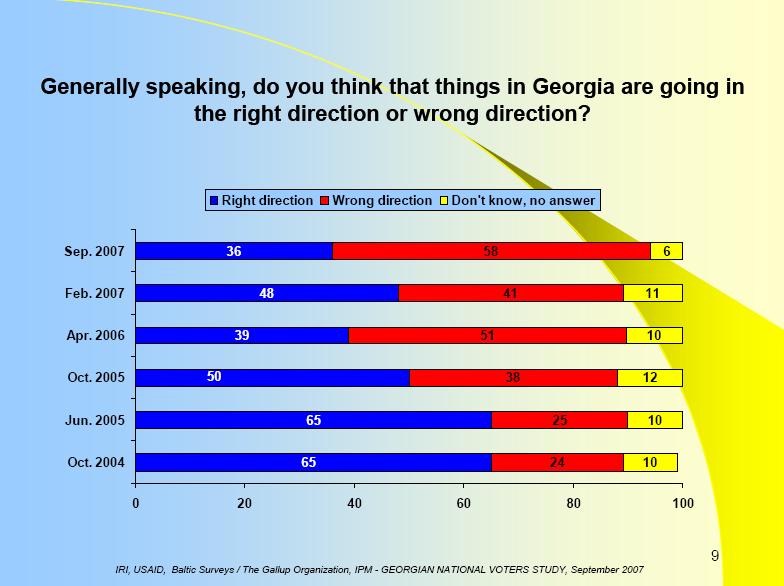

But his administration also had its fair share of scandals, and Georgians' initial enthusiasm for the young, energetic reformer faded swiftly. A survey conducted by the International Republican Institute (IRI) in September found that 62 percent of voters felt Georgia was headed in the wrong direction, a sharp turnaround from the 65 percent three years earlier who thought the country was going in the right direction.

Tom Begich, a US-based political consultant and analyst, suggested that the public unease revealed by the IRI survey could signal an uphill trek to reelection for Saakashvili.

“Based on this, the incumbent is potentially in trouble,” Begich wrote by email, adding that Saakashvili could still secure victory with a campaign which is focused on employment, steeped in patriotic values and verbally aggressive towards Russia.

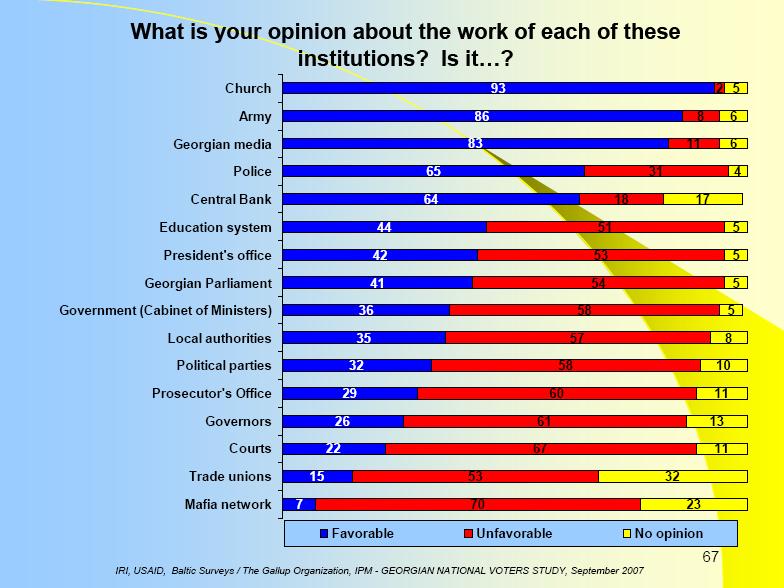

Begich suggested the IRI survey, which was carried out before the crisis of November 7 and the ensuing emergency rule and media clampdown, revealed a general distrust of the nation’s institutions. The media, however, was rated positively by 83 percent of respondents.

“Given that,” Begich said, “[Saakashvili’s] shutting down of media could have damaged him significantly more than this poll reveals.”

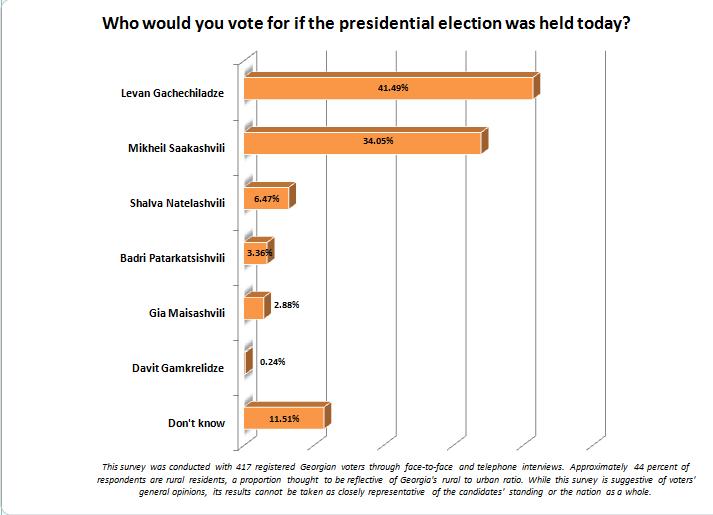

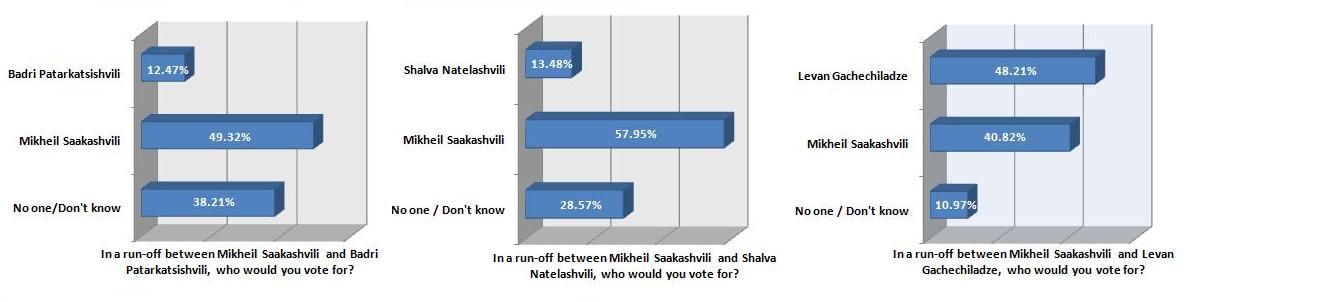

A poll conducted by the Messenger, meanwhile, suggested that opposition coalition candidate Levan Gachechiladze could pose a threat to Saakashvili in a head-to-head matchup.

If no candidate wins more than half the vote on January 5, the election will go to a run-off two weeks later. 54 percent of the poll's respondents said they would vote for Gachechiladze in a race between him and Saakashvili, excluding those who claimed they would vote for neither.

Based on these early numbers, Begich said, Gachechiladze “has a significant chance of winning.”

The informal poll was conducted with 417 registered Georgian voters. While the results cannot be taken as representative of either the country’s population or the candidates’ precise standing, according to Hans Gutbrod, Regional Director of the Caucasus Research Resource Center, it is a useful snapshot of the general mood in Georgia.

“However much people will change their opinion still…this likely will be a contested election,” Gutbrodt wrote by email. That Georgian voters are openly saying they will not vote for Saakashvili, he added, "in itself is remarkable.”

The poll, carried out from November 19-26, was conducted through a combination of face-to-face and telephone interviews in four towns and three separate rural districts. [The complete methodology and data are available here.]

The poll found little support for other candidates like Labor Party leader Shalva Natelashvili, Imedi TV founder Badri Patarkatsishvili and New Rights leader Davit Gamkrelidze. Saakashvili would win handily against any of them in a run-off, the poll suggests.

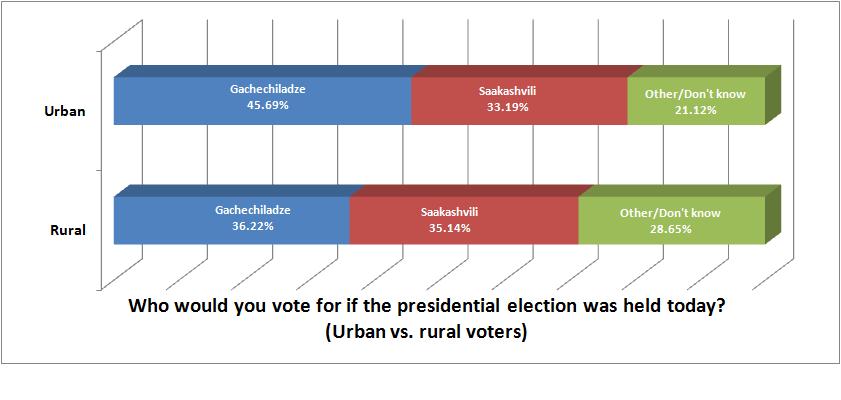

Middle-aged rural voters appeared more likely to support the incumbent. Urban voters, meanwhile, appeared to roundly prefer Gachechiladze.

Begich pointed out the data could also indicate that “the volatile electorate is the younger voter—more likely to oppose [Saakashvili]. This presents a problem for the opposition if younger voters perceive that they have no interest in the election, as they skew toward [Gachechiladze].”

The victor, he suggested, could be whoever runs the best ground game on election day.

“Given the strength in the rural area for the government, the importance of the youth vote to the opposition, and the need for the urban area to really move the opposition over the top, a strong [get-out-the-vote campaign] could make a huge difference,” Begich said.

Tina Khidasheli, a Republican leader and opposition coalition member, promised that their campaigners "are going to knock every single door" in support of Gachechiladze.

In an interview at the nine-party opposition coalition's newly opened Tbilisi office, Khidasheli claimed their own polling showed an electorate hugely eager to vote.

“72 percent [of voters] say they are definitely going, and 18 [percent] say they probably will go,” she said. “We’ve never had such high numbers.”

According to the Central Election Commission, voter turnout was over 80 percent in the 2004 presidential election.

Khidasheli predicted that Gachechiladze’s votes would mostly come from the urban and educated. Contradicting the Messenger poll, she also said she expected middle-aged voters to lean toward Gachechiladze.

The secretary general of the ruling National Movement party, Davit Kirkitadze, declined to speak about their campaign strategy.

Khidasheli said she was sure that, following the events of November 7, Saakashvili cannot win a second term. His one advantage, she claimed, is the ruling party's ability to direct government funds to campaign purposes.

“[There is a] total imbalance of the resources,” she said. “They have a [GEL] six billion budget which they can spend in any way they want.”

Khidasheli admitted that the opposition parties in her coalition are organizationally outgunned by the National Movement, but said their combined resources would be enough to mount the campaign they need.

One unanswered question is whether most Gachechiladze supporters would vote for him as a compelling presidential figure, as an alternative to Saakashvili, or as an alternative to the institution of a strong presidency.

Gachechiladze has pledged, if elected, to turn the country into a parliamentary republic and then resign. His running mate, former foreign minister Salome Zourabichvili, would then helm the government as prime minister.

Khidasheli, while acknowledging that voters will vary in their reasons for supporting Gachechiladze, maintained that ‘Georgia without a president’ is a message the electorate is looking for.

“They’re sick of idols and saviors,” she said.

Begich, the political analyst, is less sure.

“[In the IRI survey] there is an undercurrent of needing strong and forceful leadership," he said, “though ultimately Georgians want a pragmatic leader.”

But January is not just about electing a leader. When they go to the polls on January 5, voters will also be asked their preferences on NATO membership and earlier parliamentary elections - which in turn could be as crucial as who is elected to the presidency.

In previous presidential elections, there was little doubt beforehand of who the victor would be. And this January, Saakashvili is determined to shore up his shaken presidency by winning another sweeping mandate.

Yet while much can change in the next five weeks, early signs suggest Saakashvili may not only miss the resounding victory he is speaking of, but could even lose altogether. This presidential election, for the first time in Georgia’s modern history, may be a real contest.

Correction: The print version of this article incorrectly stated that 63 percent of respondents would vote for Gachechiladze in a run-off. The correct number is 54 percent, excluding voters who claim they would not vote for either.