The Economics of Language for Georgia

By Nalifa Mehelin

Monday, April 22

One of the easiest ways to communicate with money is using the language that it speaks. It becomes significantly easier in a homogenous monolingual nation, where most people speak and understand the predominantly used language. With 3.7 million native speakers, Georgian is the official language of our nation. On a national level, our Laris speak Georgian. On an international level, problems arise when Lari tries to interact with Dollar, Ruble, and Yuan. However, the commonality among all of these is English. If such is the case, to what extent Lari is prepared to talk to Dollar, Ruble, Yuan, and many more currencies? More importantly, is there such a necessity? (See the diagram. Source: EF English Proficiency Index )

With 983 million speakers including 370 million native speakers around the world, English is the second most spoken language in the world. As of 2019, English is the official language of 55 nation states. English is also a de-facto official language in Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and the United States; together with Canada which forms ‘Anglosphere’, a group which has shared historical and cultural practices. English is called the language of global business. According to The International Monetary Fund (IMF), these Anglosphere countries alone control almost 20% of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In the 2018 edition of The EF English Proficiency Index, English is said to be the corporate language, believed to create a better environment for business, reported to have a strong correlation with higher GDP growth. Not only business, with most of the academia, heavily relying on English, but it is also crucial for higher education as well. In order to perform better, learning English is now a necessity.

With the international context in mind, let’s look dynamics in Georgia now. The Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) lists the top five trading partners of Georgia. The table below shows the volume of trade among these countries. (See the table)

If we look at the data from a linguistic perspective, we only have commonality with Russia and Ukraine where we would be able to proficiently conduct business using Russian. Other than that, for diplomatic and business purposes, English is our only alternative. This should dictate a significant shift towards English language preference.

Realizing the significance of English was a pivotal shift for Georgia, due to which it initiated compulsory English language sessions since September 2011. The then Education Minister justified this long-overdue initiative saying, “In a country like Georgia which doesn't have natural gas, which doesn't have oil, our main resource [is] human. That's why education is so important for us and is so strategic for Georgia.” On one hand, this initiative equipped the population with a much needed global language skill; on the other hand, gained projecting criticism. The preference leaned more on learning Russian as a second language because of its close historical, cultural, and economic ties. However, English maintained its position in educational institutions as it is deemed to be the most popular foreign language.

Like many other initiatives, Georgia’s challenge is not tapping into a previously untested grey zone. In the grey zone of commencing compulsory English tuition, Georgia quite confidently stepped into the territory. The problem, as always, is the implementation. Any language has an internalization process which spans into four categories: reading, listening, speaking, and writing. These categories are complementary. Any contradiction to these belies the ability to grasp the subject matter and makes the internalization process quite parochial. As a result, ample resources are needed to practice each of the four processes which are considerably absent in the Georgian culture.

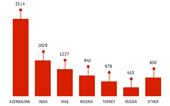

Languages require constant practice. Practicing only in schools and colleges seldom galvanize people to try and adopt new languages. Something as trivial as the minute number of English dailies in Georgia indicates the fact of resistance towards English, despite being compulsory. It is increasingly hard to conduct extensive research on Georgia if one does not have the linguistic ability. Cultural preservation is justified only when the country operates in autarky like North Korea. Georgia is the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) magnet and therefore cannot incur the same procedure as North Korea. (See the diagram2. Source: Brief Migration Profile)

Aside from developing reading habits, cultural integration and assimilation can help a lot in terms of improving listening and speaking habits. Georgia has a diverse pool of foreign students who can be used as resources to further cement English listening and speaking abilities. International Center for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), The European Union for Georgia, and Public Service Development Agency authored a joint report titled The State Commission on Migration Issues: Brief Migration Profile Foreign Students in Georgia. According to the report, as off 2016, the total number of foreign students in Georgia is 9261. The report also illustrates, “Regarding the selection of a specific university in Georgia, the foreign students surveyed tended to pay attention to the availability of courses in English, the qualification of academic staff and tuition fees.” Therefore, creating opportunities for these students to successfully assimilate in Georgia will ensure long term benefit of diversity. In the short run, these students can operate as student volunteers to practice English with.

When it comes to improving listening and speaking habits, existing ‘Learning English’ programs can also prove to be beneficial. A quick Google search unveils various ‘Teach English’ programs for native speakers. The U.S. Embassy and British Council are two of the maestros offering these programs. The idea is not to encourage the ‘White Man’s Burden’, rather it is to familiarize the practice of learning English from the native speakers. If we can bring international student volunteers and native English speakers together, it will reinforce the idea of learning by engaging which in turn will make the people familiar with the tonality and structure of the language.

In most cases, economic needs guide the way to policy approaches. When it comes to languages, it largely depends on the lingua franca of trade. Today’s context inspired me to focus on English. Tomorrow it could be Spanish or Mandarin. As long as we are flowing with the lingua franca, we have one less thing to worry about fostering trade. In the coming days, by strengthening its English language capabilities, perhaps Georgia will focus on Mandarin. Until then, it is what it is!

Nalifa Mehelin works as an Associate Research Analyst at Innovations for Poverty Action, Bangladesh.